Santo Toribio Romo, for those who haven’t been to the interior of Mexico recently, is quite possibly the most popular saint in the country. To be fair, he does face stiff competition from San Judas Tadeo (St. Jude), whose image is everywhere in Mexico City, as well as one image that looks like St. George but with a person at the end of the spear instead of a dragon (if anyone knows which saint this is, please tell me!) that is especially popular among bus drivers and taxistas. But the omnipresence of Toribio Romo’s black-and-white mug is powerful, and growing.

There are at least two obvious reasons for this popularity. One is that Santo Toribio Romo is becoming the unofficial patron saint of immigrants to the United States – especially those who cross the border on foot, without papers, under the natural threat of a deadly waterless desert and the man-made dangers of the Border Patrol, the Minutemen, and immense risk involved in choosing a responsible coyote. Is it any wonder that the God-fearing faithful, who have always cried out for divine intervention in their most dire moments, would find help from a spiritual source? For these vulnerable travelers, Santo Toribio often shows up as a guardian angel, helping the migrant through a tough spot before mysteriously disappearing into the darkness. We rationalists may scoff, but the stories – and the faith of the people – are growing.

The other reason for Santo Toribio Romo’s popularity, however, is that unlike San Judas Tadeo or the Psedo-Saint-George, Santo Toribio is certifiably Mexican. He was born on April 16, 1900, right here in the highlands of Jalisco, dirt poor. He grew up under the shadow of the Virgen de San Juan de Los Lagos, and entered the seminary in San Juan when he was only 12 years old, to be ordained as a priest by the time he was 22. But of course, by now, thanks to my endless ramblings about it, you know that the 1920s were a dangerous time to be a priest in Mexico. As the government cracked down on religious practice, Toribio Romo rebelled – not with guns and knives, but instead by continuing to administer the sacraments to his people. On February 25, 1928, government troops finally caught up with him in the town of Tequila. He was shot to death in his bedroom.

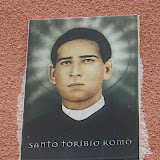

Pope John Paul II canonized Toribio Romo as a saint of the church in 2000. Twenty-four other martyrs of the Cristero Rebellion were also canonized, but none of them have yet reached Santo Toribio’s popularity. Aiding his belovedness, Chris and I have surmised, is the arresting photograph of Santo Toribio that serves as his image (see the photo at the top of this post). His eyes are almost sad, but fixed and firm, as if they are seeing his future and he is deciding in that moment that though it is not pleasant it is the path God has called him to, and he will not waver from it. Is it any wonder the saints are stand-ins for Jesus, stepping-stones to Christ?

Well. Enough background. On Tuesday I decided to visit this Mexican miracle-worker, to see Santo Toribio for myself. Chris had already made her visit with a priest in San Juan who helpfully drove her there in his car and introduced her to the priests in charge; she came home with a Santo Toribio keychain and prayer book, gifts from the administrators of the church. I, on the other hand, would be going by myself, by a series of public buses – yet another practical test of all those Spanish classes.

Santo Toribio’s shrine is in Santa Ana de Guadalupe, a tiny, tiny, tiny village outside of Jalostotitlan, a small town about two hours from Lagos by bus. Traveling through the other towns in this region helps me realize just how relatively big Lagos de Moreno really is. It is no teeming metropolis like León or Guadalajara, to be sure, and yet compared to Jalos (the popular abbreviation for Jalostotitlan) it is full of urban comforts. When my regional bus arrived in Jalos, it dropped me off at a street corner office that served as the Jalos bus station. And I thought the bus station in Lagos was small…

I walked over to the office and asked the man in an official-looking uniform how to get to Santa Ana de Guadalupe. He stared at me blankly and pointed at the corner where I had just gotten off the bus. Apparently this was the bus stop. As I was turning to go, another group of people who had been on the same bus – an friendly older gentleman and two women who seemed to be about the same age – came up and asked the official-looking person about Santo Toribio. I decided to follow these people.

We waited for about twenty minutes, and I passed the time by reading my copy of The Brothers Karamazov and trying not to look too out of place. I love traveling, but this stick-out-like-a-sore-thumb-gringo feeling is not my favorite. In a cosmopolitan city like Guadalajara, where airplanes arrive daily from foreign lands, I hardly ever feel it, but here in a rural town you really feel like a stranger in a strange land. Of course it’s a thrill, but it can be a bit terrifying all the same.

When the little bus arrived, I and my (unsuspecting) traveling companions got on board and we all rattled our way out of town. As we made our way out into the countryside, the smells became more and more pronounced. You know what I mean. Farm smells. Cow smells. Nebraska smells. Iowa smells. This was a long way from Mexico City.

We turn down a dirt road and pass under a stone arch that announces the place of Toribio Romo. There is nothing but dry grass and desert trees around this shrine; nothing is visible from here. I wonder if this is what the arches in Guadalajara were like before they were swallowed up by the growing city. I wonder what this place will look like in 10, 20, 50 years. Will it be like San Juan de Los Lagos, pumped up to a sprawling size by the development steroids of cash brought by faithful pilgrims from across North America? People in San Juan call their town’s economic health the “true miracle” of the Virgen; will Santo Toribio deliver the same economic miracle to his hometown?

If it will happen, it hasn’t happened yet. The bus driver – who is extremely friendly – drops us off at a street corner, but I don’t see anything resembling a church. This is nothing like San Juan de Los Lagos, a mad market of religious souvenirs leading to a towering basilica that is visible for miles around. Not wanting to seem uncertain, I spot a weathered tourist sign and walk firmly toward it. It’s the right move – when I reach the sign, I immediately see the stone church around the corner.

It’s almost shockingly small. Later I discover that Padre Toribio built this church himself, organizing the people and resources to get a church built in his hometown. This explains the church’s size, but still: This is the land of massive parish churches and towering basilicas stuck in the middle of small rural cities, yet the shrine for one of Mexico’s most popular saints is a tiny stone sanctuary far outside of town.

As I walk through the church doors, a woman next to me drops to her knees, and then begins shuffling up to the altar. What is it with this shuffling up to the altar on your knees thing? People do it in San Juan, too, and I’m always bewildered by it. On the one hand, it’s beautiful piety, a powerful expression of devotion that even a Protestant can’t help but respect. On the other hand, what kind of God – or Virgin or saint – wants you to shuffle up to their throne on your knees? I understand it rationally – puny human before powerful deity – but this physical submissiveness doesn’t exactly make me feel full of love for the Lord.

On the other other hand, I continue to be amazed by the Mexican faithful’s use of physical acts in their religious practice. From the Christmastime posada parades to the outdoor theater of Good Friday, Mexican Catholicism gives you something to do and not just something to think. I’ve come all the way out to see Santo Toribio – now what? I can pray silently in my head, and I do, but as I watch the woman shuffle up to the altar I find myself wishing I had something physical and physically demanding I could do during my pilgrimage, to cap it off. I make a note to file this away for further reflection later.

Outside, in the “backyard” of the little church, I find a long walkway leading to another little church. This is the Calzada de los Martires, or Walkway of the Martyrs. All along the little stone path there are cement busts and inscribed plaques to the other Cristero martyrs. Most of them are from Jalisco, but there are a few from Zacatecas, too, and at least one each in the northern border states of Durango and Chihuahua, and one, I am surprised to find, from the southern state of Guerrero. (Question: Why is Santo Toribio the patron saint of migrants, and not one of the martyr saints from a border state?)

In the middle of this walkway, there is a monument to Christ the King and the Virgin of Guadalupe, a visible rendering of the Cristero martyrs’ final cry: ¡Viva Cristo Rey y la Virgen de Guadalupe! Long live Christ the King and the Virgin of Guadalupe! The monument itself is a curious one. There is a black cross. On one side of the cross is Jesus, his arms up in the air and wearing the cloth of resurrection – this is “viva Christo Rey.” On the other side of the cross is the Virgin of Guadalupe, life size. They are positioned like two sides of the same coin – or two sides of the same cross. I have no idea what this means theologically, but it’s got to be worth a paper or two in a systematic theology class.

At the end of the walkway is another stone church, about the same size as the first one. Later Chris tells me this other church was built by Santo Toribio’s family after his death. Next to the church is a replica of Toribio Romo’s childhood home. It’s like one of those 18th or 19th century homes you can visit in certain national parks (there’s one in my grandparents’ town in Iowa), complete with furnishings from the era. This one is about the size of the living room in our apartment in Lagos. Later Chris tells me that Toribio Romo’s parents raised five kids in this one-room log cabin. The point, she tells me, is that they were dirt poor. I try to take a photo of the house, but it’s difficult to capture without the fancy restaurant built just behind it.

On my visit I miss the retablo room, where visitors put thank-you notes, thank-you paintings, and random thank-you items like soccer jerseys on the walls as an offering of gratitude to Santo Toribio. Chris tells me that on her visit one retablo struck her especially: A family gave thanks to Santo Toribio Romo for helping them to finally find the body of their daughter who had died in her attempt to cross the border. For these parents, the miracle was that their daughter did not disappear in the desert like so many other sons and daughters who perish in the wilderness; against all odds, they found her body, they could bury her, they could have closure.

As I leave the place of Santo Toribio, I notice his photo over a doorframe on a nearby house. The Christian faith represented by this devotion is so different from the Christian faith that I grew up with. Yet it is faith all the same, a powerful, fierce faith, strong as any I have encountered elsewhere. What does God see when he looks at this faith? What do you see, O Lord?

I have spent so much of my time parsing the differences between my faith and the faith of the people all around me; throughout my time here I have struggled to make sense of it all. But there are moments - moments, I think, when the truth beyond my brain breaks in - when my heart is pierced by what I can barely understand. And it's times like this when, well... when it brings me to my knees.

I sat on the side of the road for an hour and a half waiting for the little bus to come back and take me home. When it finally did, it was in the middle of the loop to a nearby town, so I rode the bus from Santo Toribio's rural church to San Miguel el Alto and then back to Santo Toribio and then finally on to Jalosototilan, where I caught another bus to San Juan de Los Lagos and finally back to Lagos de Moreno, another long day come to an end.

|

| Santo Toribio |

1 comment:

I've also done my pilgrimage to Santo Toribio Romo, and like the others, I also shuffled along the walkway on my kness to give thanks for a different reason: keeping me positive throughout my cancer treatment. Most of my family on my father's side is from Jalos, and as you can imagine this faith trickled down to me.

Ironically, I'm one of those who questions his own faith, and the witnesses that have come across Santo Toribio Romo. On one hand I love the message I grew up with - it's mostly positive. On the other hand, you have other Christian faiths that really stand on negative ground (e.g. I'm a homosexual, therefore I'm a sinful person), which I completely disagree with. It ultimately makes religion a hypocrisy. Yet, I haven't entirely given up on it.

On a side note, this is a great post. Really makes me want to go back to Jalos. Just so you know, you could fit into these towns around Los Altos. Half of my family members there have blonde hair and blue eyes. Even I, who couldn't be anymore Mexican with dark hair and fair-colored eyes, stuck out in Guadalajara, when I was called a "gavacho" by one of the marketplace employees. It's a derrogatory term for Americans.

Post a Comment